2023 Conference: Panel Recaps

Education's Fiscal Cliff Following ESSER

By Mebane Rash,

CEO & Editor-in-Chief, EducationNC

Researchers discuss different strategies for school districts facing the federal funding cliff

As school districts nationwide face a federal funding cliff, government researchers from independent think tanks around the country met in Worcester, Massachusetts, to discuss how municipalities and states are preparing.

Since 1914, the Governmental Research Association has been connecting researchers working to improve their communities. This year’s annual conference was hosted by the Worcester Regional Research Bureau.

During the pandemic, the federal government issued three tranches of funding totaling $190 billion for school districts. Districts spent this money on everything from one-time costs like HVAC upgrades to recurring costs to address learning loss and student wellness.

The last round of funding must be committed by Sept. 30, 2024 — just a little more than a year from now.

Districts can request 18-month extensions on spending the funds and even longer in extraordinary circumstances. But for most districts, the fiscal cliff is looming large.

It’s the loss of federal funding that’s being used to pay educators that has researchers nationwide concerned. When this money goes away, districts will either have to get funding from other sources or cut back.

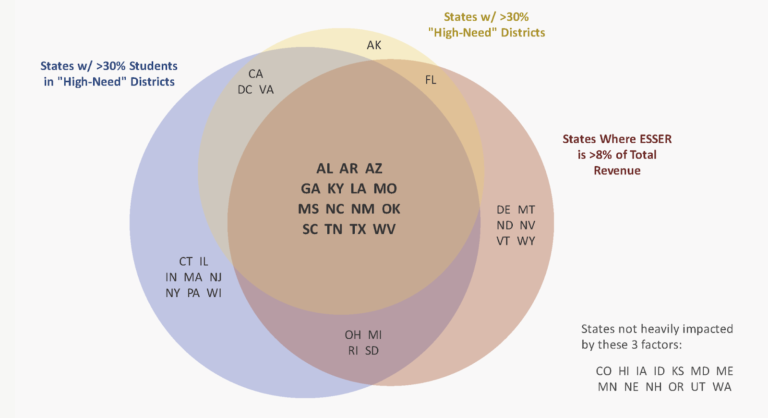

A report issued in March identified 15 states facing the most complex challenges with the fiscal cliff.

Massachusetts has a statewide strategy to increase funding for schools that should help districts cope.

In the months ahead of the pandemic, the state had been preparing to implement the Student Opportunity Act, a school funding law passed in November 2019.

“COVID derailed the first year of the plan,” said panelist Colin Jones, a senior policy analyst for Massachusetts Budget & Policy Center. “In the beginning, it wasn’t clear — particularly for the low-income districts that were the targets of the reforms — that they were going to get more federal aid than they were losing by delaying the plan.”

“There is a false narrative,” Jones said, “that districts are sitting on piles of cash.”

That narrative is complicated by the fact that Massachusetts hasn’t passed a state budget for 2023-24 even though the fiscal year started July 1, he said.

“As ESSER fades away, we have to go back to where we were heading,” Jones said. “States have to assume they are on their own.” He noted that the toughest part of the conversation for states that want to address the cliff is where the revenue will come from.

Panelist Alexis Lian is director of policy for the Rennie Center for Education Research and Policy, which is part of EdImpact, a research consortium “designed to support evidence-based spending, analyze the impact of COVID recovery funds and provide a platform for the field to learn from one another and reflect on progress made.”

EdImpact launched 24 data dashboards for districts in Massachusetts showing planned investments of the federal funding, finding investments focused on academic recovery, including high-dosage tutoring, acceleration academics and high-quality curriculum; and on social emotional and mental health, including implementing Tier 1 of the Multi-Tiered System of Supports, SEL curriculum and mental health literacy.

Lian said “90% of district decisionmakers cited challenges deploying stimulus funds.”

For comparison, McKinsey surveyed 260 school districts nationwide to see how they deployed federal funding.

As of July, Lian said, in Massachusetts all of ESSER I funding has been committed, 82% of ESSER II and just 33% – $1.1 billion – of ESSER III.

“There is an enormous amount of money to still allocate,” said Lian. “Districts are working incredibly hard to make really difficult, strategic final decisions.”

Based on their work with districts, EdImpact issued six takeaways for investing the remaining funds, including a coordinated statewide approach to prioritize investments that impact students and can be scaled.

Panelist Jason Stein, vice president and research director of the Wisconsin Policy Forum, said “one important learning from the Wisconsin experience is that as legislation like [the American Rescue Plan] gets debated at the federal level, it can still play out at the state and local level in very different ways from the original intent.”

The federal legislation authorizing funding contained a maintenance-of-effort provision intended to keep states from reducing their support for public education.

Stein said his state has revenue caps that limited the revenue districts could receive the last two years, so there was no increase in state funding. “It was in reaction,” he said, “to a perception that districts were getting so much federal money that there was no need for the state to do its typical funding.”

Many districts in Wisconsin went on to pass referenda, Stein said, with voters opting to raise their own taxes to increase school funding.

Making national news, Gov. Tony Evers, a Democrat and a former teacher and state superintendent, used his partial veto power and some ingenious editing of the proposed state budget to institute a $325 funding increase per student for the next 400 years — through 2425.

In North Carolina, where the 115 school districts are facing the fiscal cliff and other threats to enrollment and funding — including a proposed expansion of school choice — EdNC is looking at district fund balances, which operate like savings accounts, and public school foundations in Durham and Charlotte as tools for districts to cope with revenue pressure, whatever the cause.

An actual boots-on-the-ground perspective of the federal funding cliff was shared with researchers by panelist Sara Consalvo, budget director for the Worcester Public Schools.

According to Consalvo, her district used federal money to bridge funding for the state’s Student Opportunity Act, stabilize funding because of changes in enrollment, upgrade and maintain ventilation systems in 44 schools, address learning loss through summer school and afterschool programs, purchase personal protective equipment and technology, and acquire a fleet of new yellow school buses.

"STEM-ing into summer!" Students at Jacob Hiatt's Summer Program are using hands on activities design to strengthen Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) learning. The curriculum also focuses on the importance of working together. pic.twitter.com/D320oCuFYG

— Worcester Schools (@worcesterpublic) July 21, 2023

The district, which had previously contracted for school bus services, received permission to purchase 165 buses.

“It’s been an absolute success,” Consalvo said of this one-time investment.

The upsides of spending made possible by the pandemic relief funding are held in tension with the reality of the federal fiscal cliff for both district leaders and the researchers watching this drama unfold.

“As school district leaders look to their 2024 budgets and beyond,” says a report called “Up in the Air” by the Wisconsin Policy Forum, “many see that a key lifeline is fraying and about to break.”

Follow Mebane Rash on Twitter at @Mebane_Rash.

GRA strengthens government research through peer relationships. Start connecting today.